The Rocks Remember: What the Rovers Have Taught Us About Habitability on Mars

Image: Caltech/NASA-JPL

by Sabrina Pirzada

In 2012, NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, managed by Caltech, delivered a car-sized rover outfitted with a full geochemistry laboratory to the surface of Mars to investigate a question that has persisted across generations: whether the planet has ever sustained the conditions necessary for life.

More than a decade later, the Curiosity rover continues its ascent of Mars’s Mount Sharp. During a recent Watson Lecture, Ashwin Vasavada (PhD ’98), project scientist for the mission, reflected on what the rover has revealed about the Red Planet, and how those discoveries continue to reshape our understanding of planetary habitability.

Follow the Water

The search for life begins with the search for water—specifically long-lived liquid water, one of a handful of key ingredients that make life possible. Clues that liquid water might once have flowed on Mars appeared in 1971, when photographs taken by Mariner 9, the first spacecraft to orbit another planet, revealed dry river valleys and flood channels carved into the cratered plains.

“It was the first actual scientific foundation for thinking that life may have been possible on Mars, at least in its ancient past,” Vasavada noted. Subsequent missions would deliver overwhelming evidence that water had indeed existed on Mars, prompting the scientific question Curiosity was designed to answer: Was Mars ever a habitable planet?

Journey to the Martian Mountain

As Vasavada noted, “The history of a planet is recorded in its rocks.” And it was within Martian rock that Curiosity would search for the other ingredients that life requires: key chemical elements and organic molecules, along with evidence of past liquid water and energy sources that could have supported microbial life.

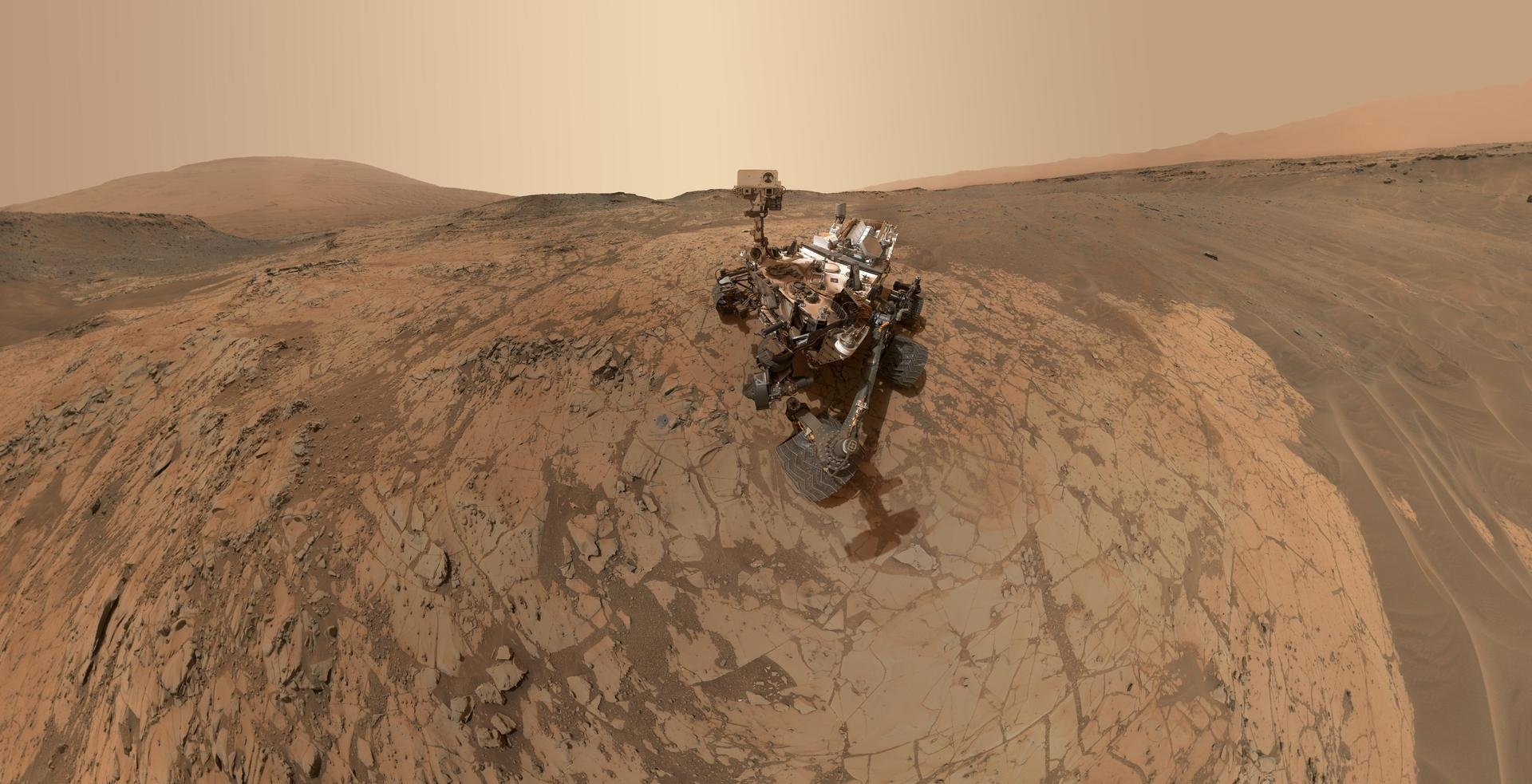

This view from the Mastcam on NASA’s Curiosity rover reveals rock formations and finely layered terrain along the lower slopes of Mount Sharp. Credit: Caltech/NASA-JPL

At the center of Gale Crater, Curiosity’s landing site, stands Mount Sharp, a 5-kilometer-high stack of sedimentary rock layers—informally named for Robert Sharp, former chair of Caltech’s Division of Geological and Planetary Sciences. Each layer preserves an interval of ancient Martian time. Sediments transported by wind and water settled in succession, forming an archive that spans billions of years. “By studying those layers, you can read the history of a planet like a book ... and understand what the planet was like era by era, 3 to 4 billion years ago,” Vasavada said.

Images from the Mastcam aboard NASA’s Curiosity rover show a series of sedimentary deposits in Gale Crater. These sediments settled and hardened long ago, preserving evidence of Mars’s ancient environments and the changes that shaped the planet over time. Credit: Caltech/NASA-JPL

When Curiosity began its work on the floor of Gale Crater, the first drilled samples revealed a lake environment with clay minerals, neutral-pH chemistry, and low salinity (“All good news for any microbes that might have been living there,” Vasavada said) as well as carbon, nitrogen, and other essential elements. The discovery confirmed that Mars had not only hosted water but that life was indeed possible there. While this satisfied the mission’s initial objective, it also opened the door to deeper questions. How long had habitable conditions persisted? How did conditions change over time? Were habitable conditions isolated or widespread across the planet’s history?

As Curiosity began its ascent of Mount Sharp, the scale of the mountain’s history became more apparent. The lower slopes of the mountain consist of finely laminated layers that likely formed on the floors of long-lived lakes. The repetition of these layers, which number in the hundreds of thousands, suggests that liquid water persisted for intervals far longer than originally imagined. This record also contains the signature of a profound planetary transition: Higher on the mountain, clay minerals give way to sulfate-bearing sandstones. Such a change reflects the gradual drying of the planet as its atmosphere thinned and surface water became scarce, leaving behind landscapes shaped by wind rather than by standing lakes.

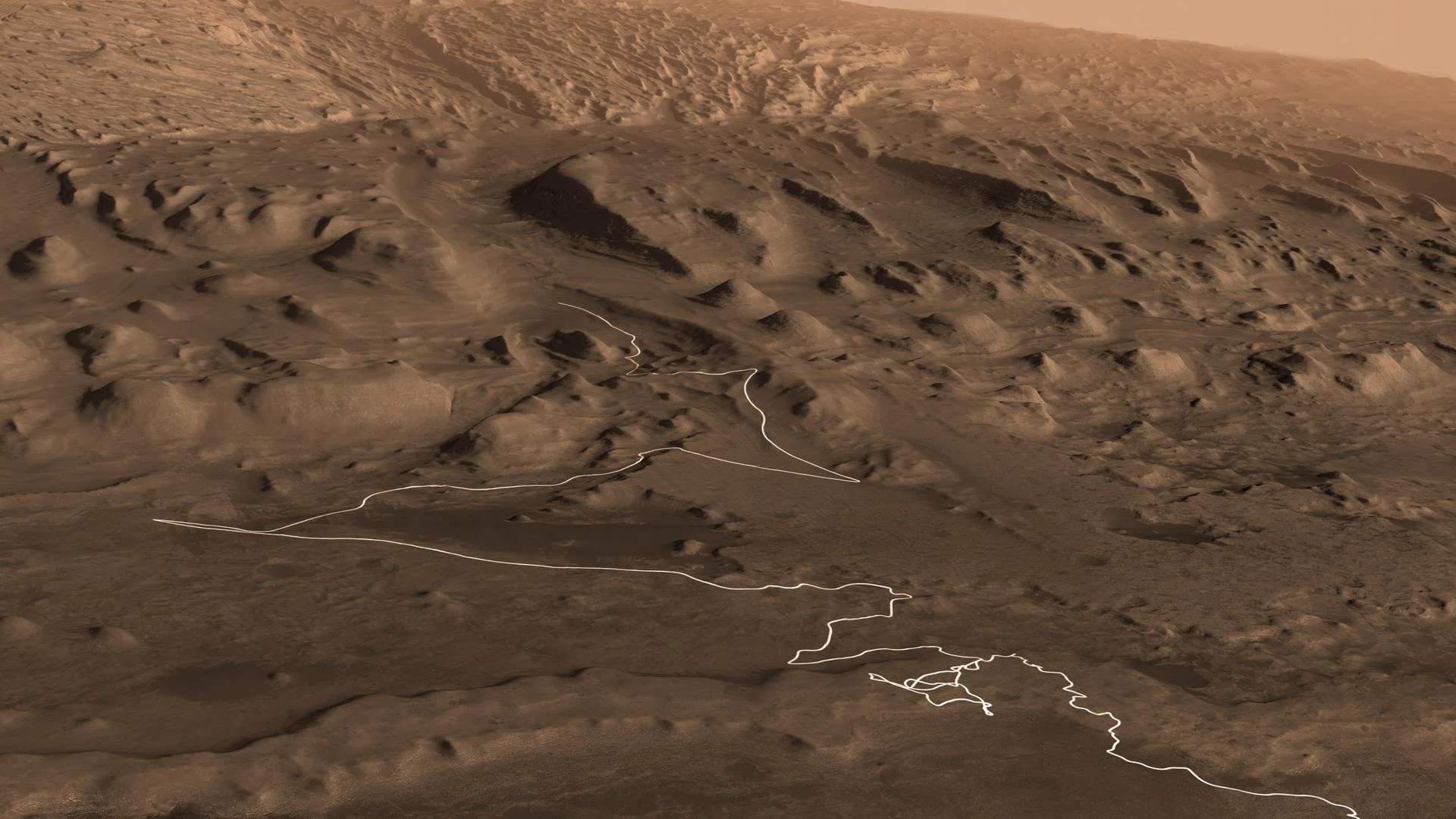

The route planned for NASA’s Curiosity rover as it climbed Mount Sharp. Credit: Caltech/NASA-JPL/ESA/University of Arizona/JHUAPL/MSSS/USGS Astrogeology Science Center

The climb brought discoveries that surprised even the mission team. In one region, Curiosity encountered wave ripples preserved in stone, an indication that some lakes remained uncovered by ice and were stirred by wind. In another, the rover crossed what was once a river channel, cut into rocks that themselves formed long after Mars was thought to have entered its arid phase. These findings suggest that the climate history of Mars may have included episodic returns of liquid water, adding complexity to the story. Most enigmatic of all was a deposit of pure elemental sulfur, a mineral occurrence that researchers have not been able to explain given the lack of volcanic or hydrothermal activity on Gale Crater.

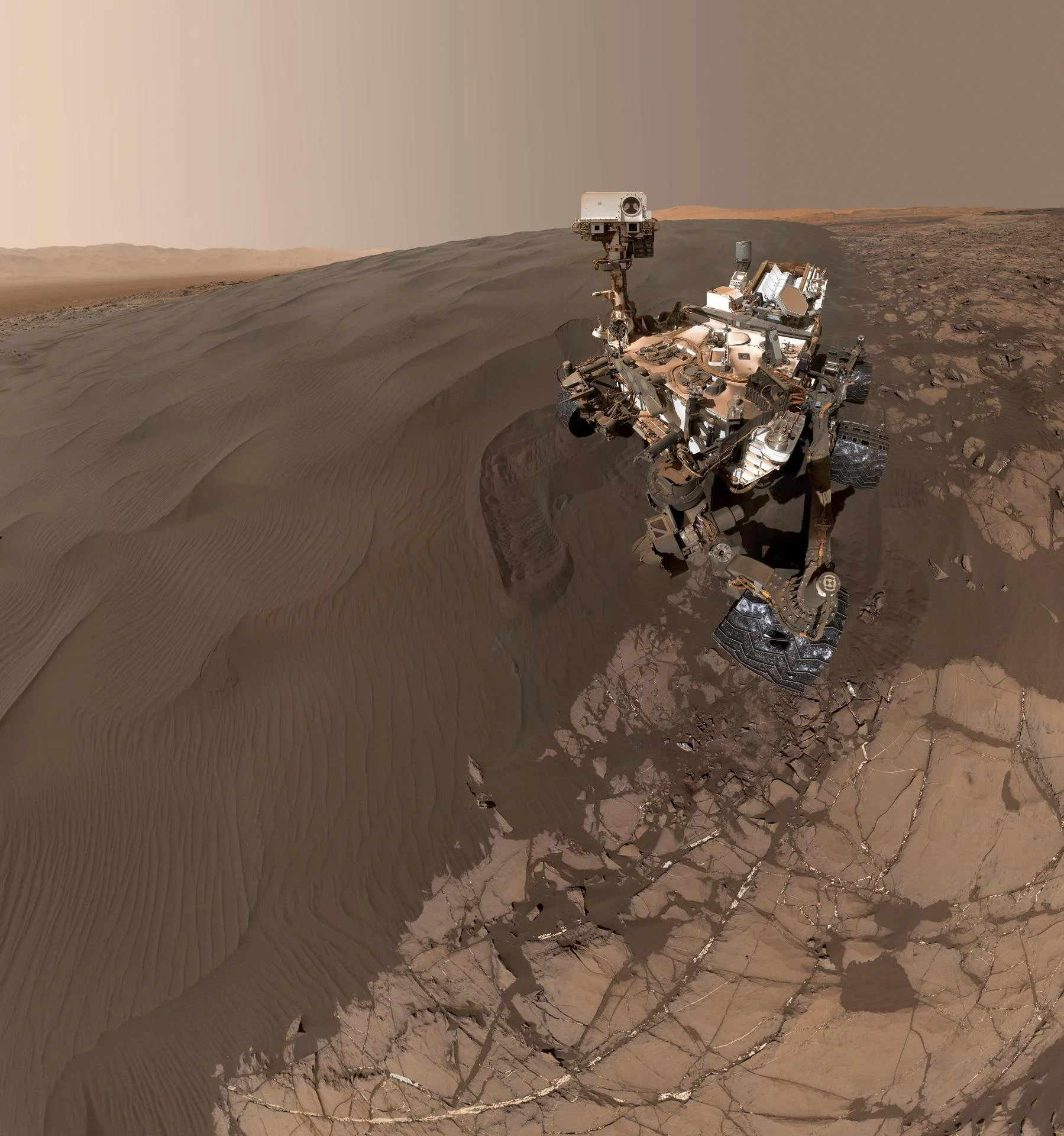

Curiosity’s selfie on Mount Sharp. Credit: Caltech/NASA-JPL

What It Takes (And Why It’s Worth It)

“I remember walking back to my office that night after celebrating the landing with the team,” Vasavada said of the 2012 touchdown of Curiosity on Mars, “and feeling like this giant spotlight that had been on the engineering team for not only this night but the decade was shifting over to the science team, and NASA and the world would be waiting to see if what we discovered was worthy of all it took to get this rover to Mars.”

The discoveries that have arrived in the years since offer a clear answer to that question. The mission demonstrated that the ingredients associated with life were present on Mars and that environments capable of supporting life endured far longer than imagined. “We were sent to figure out if we could find a habitable environment on Mars. And we didn't find just one. We found a record of habitable environments that probably lasted millions of years. And the quality of those environments, I think, far exceeds even our highest hopes for what we might've thought we would find on the day we landed,” said Vasavada.

The work on Mars also allows researchers from campus and the lab to illuminate the history of Earth. Mount Sharp offers a lens on planetary change that sharpens the models used to understand the forces that shape climates across worlds. Additionally, missions of this scale cultivate the next generation of astronauts, researchers, engineers, and thinkers, who carry their skills into fields ranging from energy and national security to computing and environmental science.

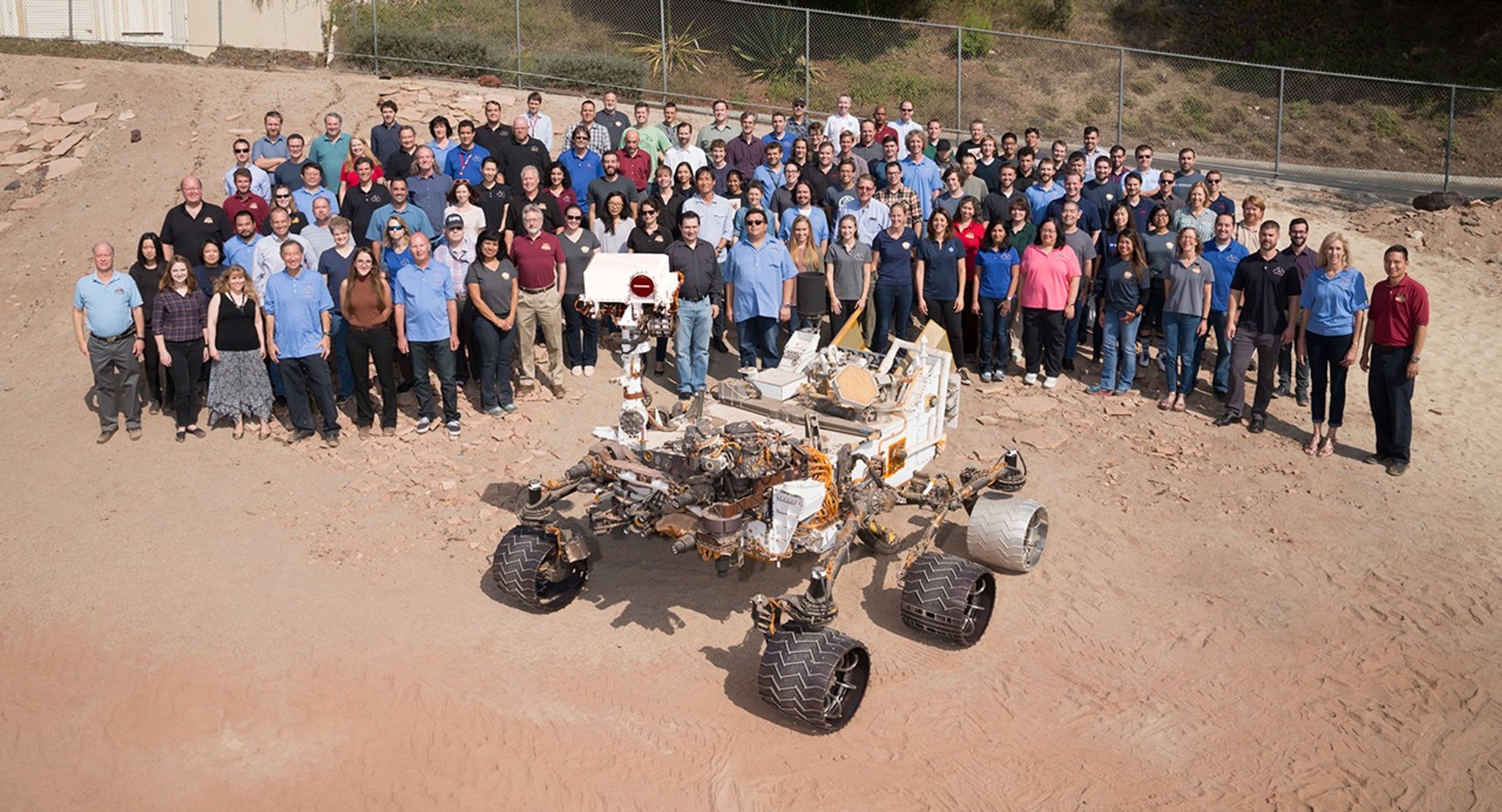

Members of the team gathered with a test rover in the “Mars Yard” at JPL. Since development began, more than 7,000 people from at least 33 U.S. states and 11 countries have contributed to this mission. Credit: Caltech/NASA-JPL

The investigation continues, shaped by the belief that careful inquiry can reveal not only the history of another world but insights that inform our understanding of this one. Just as Mars keeps its history in rocks, Earth keeps ours, also, in what we leave behind—marking that we looked outward, hoping to understand our beginnings and our place among what is possible.

This article was adapted from Ashwin Vasavada’s November 2025 Watson Lecture. Watch the full lecture below, or on YouTube.