A Snowflake for the Record Books

The world's largest snow crystal, measuring about 1 centimeter from tip to tip. Kenneth Libbrecht took this photo in northern Ontario, Canada, in 2003.

by Whitney Clavin

More than 20 years ago, while out taking photos in chilly northern Ontario, Canada, Ken Libbrecht (BS ’80), a Caltech professor of physics, noticed enormous snowflakes drifting down all around him.

"All of a sudden, I saw these huge snow crystals," says Libbrecht, who says the event lasted about 10 minutes. "I could look around and see them with my naked eyes. I'll never forget it."

Although that wintry wonderland moment occurred decades ago, one of the snowy specimens Libbrecht photographed that day officially remains the world's largest documented natural snow crystal, a six-sided beauty that measures about 1 centimeter in size.

"You need special conditions to make them that big," says Libbrecht, who studies the dynamics of ice crystal formation. "Temperatures need to be about 5 degrees Fahrenheit and the weather needs to be high in humidity and extremely calm with no wind. Any wind can break them up."

A typical snow crystal is about 2 to 3 millimeters in size. The term “snowflake” is often used more broadly to describe collections of snow crystals stuck together, or what Libbrecht calls "puff balls." In fact, for decades, Guinness World Records listed a 15-inch snowflake discovered in 1887 as the world's largest, but Libbrecht knew that must have been a puff ball and not an actual snow crystal.

A few years ago, he decided to finally do something about the misleading record and contacted Guinness. After spending many weeks verifying the authenticity of Libbrecht's snow crystal photo, the organization officially changed its entry to reflect his world record.

To this day, Libbrecht's snow crystal is the largest photographed in nature, though he says there are surely larger ones out there that will eventually supersede his rare find.

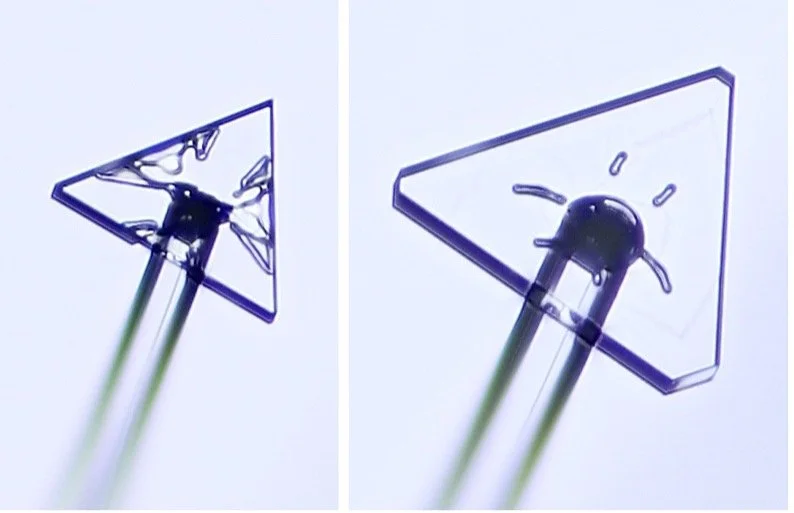

The image on the left shows a triangular snow crystal created in Libbrecht’s lab, supported by a long ice needle. The three sides of the triangle are each just 0.165 millimeters in length. The image on the right shows the same crystal grown to a slightly larger size. Both pictures are the same scale.

In more recent work, Libbrecht solved the mystery of triangle-shaped snow crystals, a phenomenon that had been documented for over 150 years but never explained. Though these geometric wonders are in fact six-sided, three of their sides are so short that the crystals appear as triangles. To find answers, Libbrecht went back to what he refers to as his "grand unified theory" of snowflake formation to see if it might explain how the triangles form. The theory led to the prediction that the triangles should form at 6.8 degrees Fahrenheit (-14 degrees Celsius) and at a supersaturated humidity level of 107 percent. Sure enough, the triangles formed as predicted under these laboratory conditions.

"I observed almost 100 percent triangular snow crystals in the lab," Libbrecht says. "This was very satisfying. I developed the model with other things in mind, and then it applied to triangles. When your theory predicts something that you didn't expect it to predict, that's a good sign."