How Tabletop Quantum Experiments Could Answer the Question of Why We Exist

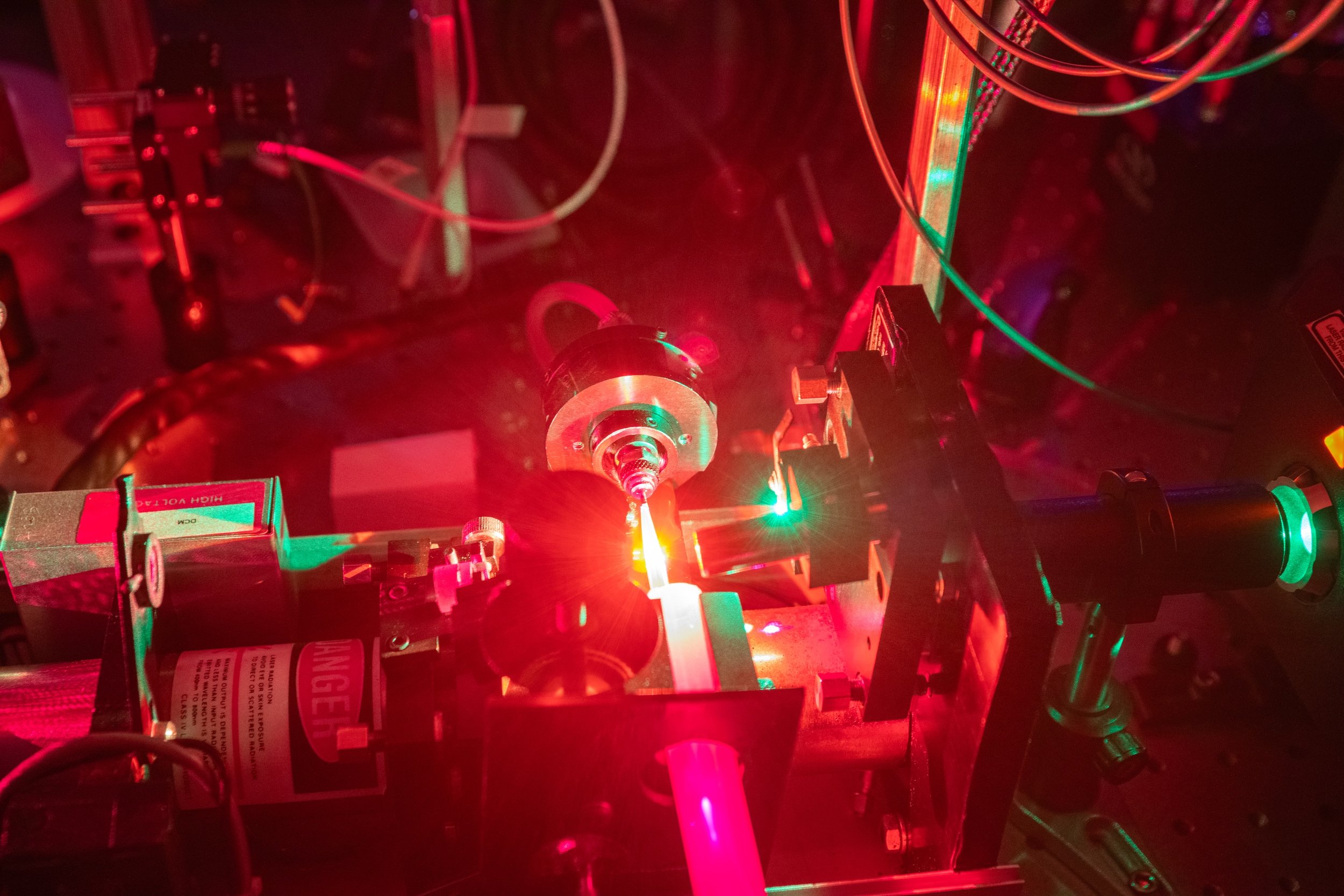

Photo: Lance Hayashida/Caltech

The Big Bang should have created equal parts matter and antimatter. Caltech’s Nick Hutzler (BS ’07) wants to know why it did not.

by Sabrina Pirzada

According to the fundamental laws of physics, we should not exist. When the universe began, the big bang should have produced matter and antimatter in perfect balance. And when matter and antimatter meet, they annihilate one another, turning into pure energy. So, the existence of anything at all—planets, stars, life—means that something happened to break the symmetry.

Nick Hutzler (BS ’07), an assistant professor of physics at Caltech, and members of his lab are searching for an answer to that question: Why does the universe contain anything at all? To learn the secret as to why the universe chose matter over antimatter, Hutzler’s team must catch the universe breaking its own rules. To do so, they are zooming in on the tiniest particles in existence.

While some physicists hunt for answers using massive particle accelerators, Hutzler and his lab use a compact tabletop setup designed to measure molecules with extraordinary precision. “If you look closely enough at an electron, you'll see it surrounded by a quantum fireworks show, a cloud of particles flickering in and out of existence,” says Hutzler. “This cloud contains every possible particle including undiscovered ones, including the symmetry-violating ones, the ones that might explain why the universe chose matter over antimatter. Finding the perfect molecule will help us study electrons and nuclei better than ever before through the use of quantum science tools,” and with the unlikely help of watch sellers on eBay.

Radioactive, Unstable, Poisonous—And Perfect

The first step in the experiment is choosing a molecule most likely to reveal the physics Hutzler’s team is hunting for. “First, we make a wish list,” says Hutzler. “We start at the chalkboard and then take all of these design elements and try to combine them into a molecule that we can actually work with in the lab.”

The lab works with molecules that are hard to find. Radium monohydroxide (RaOH) is one of them. It checks all the boxes on their wish list: a very heavy nucleus that can greatly amplify any tiny, still-undiscovered symmetry-breaking effects; the ability to be controlled and measured with lasers; and strong protection from electromagnetic interference.

Most atomic nuclei are nearly spherical, but a very small number, like radium, have a rare, asymmetric “avocado” shape. This can amplify the effects of hypothetical symmetry-breaking forces by roughly a factor of 1,000, making them powerful tools for searching for new physics. Credit: Courtesy of Nick Hutzler

It also fulfills one more unusual requirement: It has an avocado-shaped nucleus. Most atomic nuclei are nearly spherical, but a rare few are squished in a way that boosts the sensitivity of these tests. Radium is one of the very few elements with this rare nuclear geometry. One problem: It’s also radioactive, chemically unstable, poisonous, and, prior to Hutzler's work, largely unstudied in molecular form.

“But otherwise, it’s perfect,” Hutzler says.

From Telling Time to Explaining Time

Vintage watch hands purchased on eBay provided an early source of radium for Hutzler’s experiments. Before its dangers were known, radium was commonly used to make watch dials glow in the dark. Credit: Courtesy of Nick Hutzler.

Obtaining radium for these experiments presents its own challenges. Once handled casually, radium is now understood to be so hazardous that only a handful of special facilities are allowed to produce and distribute it in trace quantities.

Hutzler’s search for radium led the lab to an unusual supply chain. In the past, before people understood how dangerous it was, radium was widely used to make watch hands glow in the dark. So, Hutzler’s team turned to watch-repair suppliers on eBay to find vintage watch hands painted with glow-in-the-dark radium paint. These were used for initial testing and have since been replaced by scientific samples from Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

Inside the lab’s “mini fridge,” radium monohydroxide molecules are cooled in helium gas until they are stable enough to be studied. Credit: Courtesy of Nick Hutzler

Once procured, these tiny, intensely radioactive samples were then handled in Caltech’s specialized isotope lab. But gathering radium is only half the battle; making the molecule safe enough to study has proven extraordinarily demanding. RaOH is so reactive that it will interact with all solid materials: air, water, and even itself. “One of the steps is dissolving it in a high-temperature acid. And so, our group attracts the type of people who are like, ‘Oh, we have to work with hot, radioactive, poisonous acid? Sign me up,’” Hutzler says.

Not only that, says Hutzler, but "the only place that you can reasonably work with a molecule like this is in an inert gas, like helium, cooled to minus 450 degrees Fahrenheit." Thus, the work happens inside what the lab members fondly call "the mini fridge," a copper box filled with helium gas and cooled to extremely low temperatures. In that frigid helium environment, RaOH molecules are stable enough to study. It is only then that the hunt can begin. The team looks for tiny shifts in electrons that will appear if the symmetry-breaking particle or force they’re looking for shows itself.

The answer to why the cosmic scales were tipped in favor of matter may lie within a force, a particle, or some other form of energy. Nobody knows exactly which form this will take, which is why Hutzler believes his versatile molecular approach, sensitive to a wide range of possible explanations, holds such promise.

In past eras in the history of physics, new particles were predicted before they were found. For the mystery of matter versus antimatter, there is no such roadmap. “We don't really have a good idea of what else is out there, which is kind of an unusual situation for physics to be in,” Hutzler notes. The answer to why we exist, why there’s something rather than nothing, might be hiding in the subtle flicker of a symmetry violation, waiting to be revealed by molecules dancing in the glow of a laser beam.

This article was adapted from Professor Nick Hutzler’s October 2025 Watson Lecture. Watch the full lecture below, or on YouTube.