Insulin Innovator

Credit: Leah Lee.

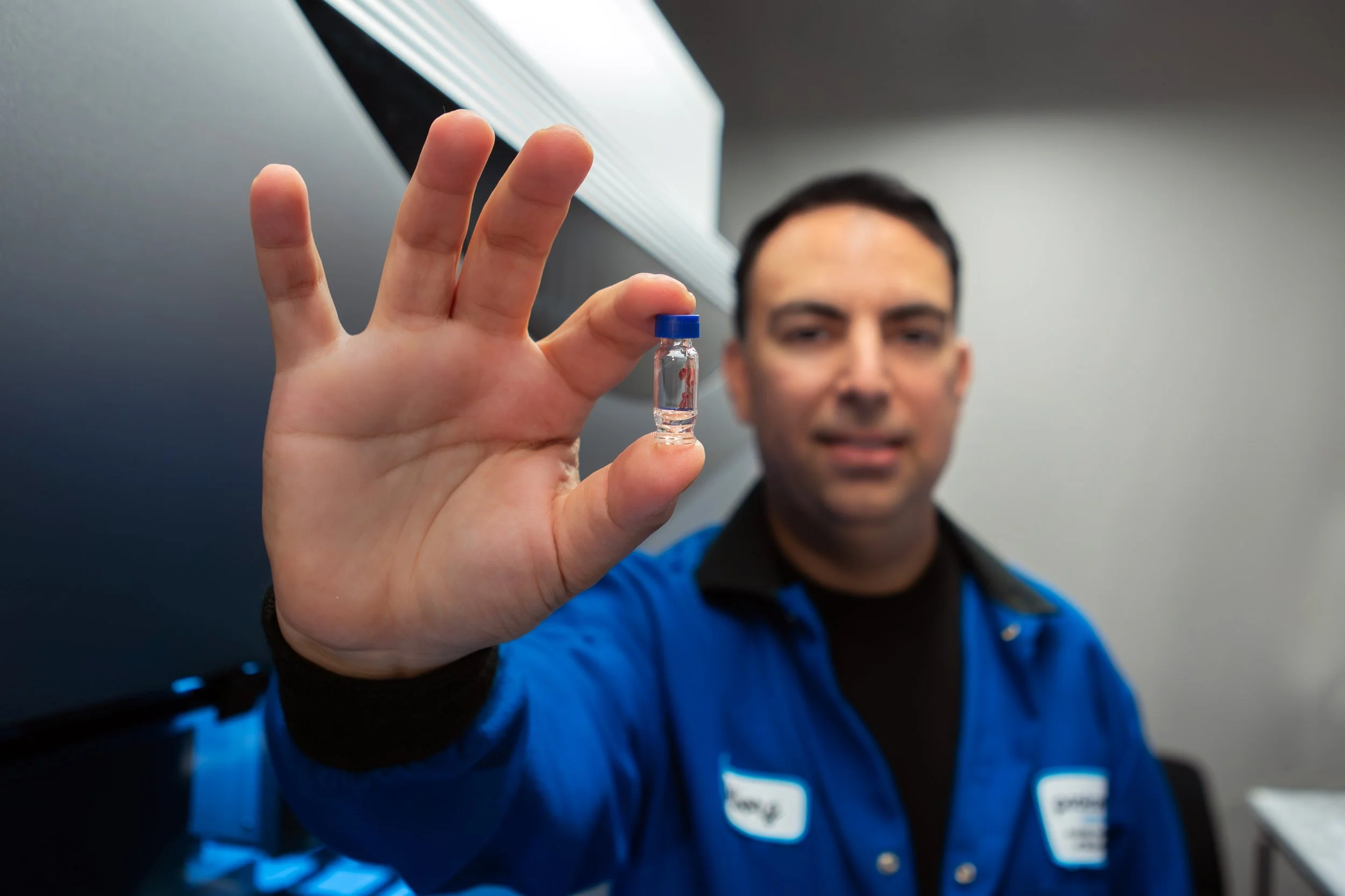

Caltech alum Alborz Mahdavi (PhD ’15) aims to revolutionize type 1 diabetes treatment in the heart of Pasadena.

By Marisa Demers

Nearly 10 million people around the world living with type 1 diabetes must perform a daily series of finger pricks, injections, and insulin pump applications in order to manage their condition. As a bioengineering graduate student at Caltech, Alborz Mahdavi (PhD ’15) believed molecular science held the power to transform the treatment of diseases. He was especially drawn to the scientific challenge of diabetes treatment and how to mimic biological processes for glucose management.

“This was a perfect problem for someone from Caltech to take on because it’s so technically challenging that most people would essentially write it off as impossible,” says Mahdavi, who studied with David A. Tirrell, the Ross McCollum-William H. Corcoran Professor of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering. “It was a problem that needed not only a solution but an elegant one. Building an extremely complicated molecule wouldn’t be practical for industry.”

While at Caltech, Mahdavi heard about the Grand Challenge Prize being offered by Breakthrough T1D, a nonprofit seeking innovative molecular-level designs for a new type of insulin that could sense major swings in blood sugar levels and trigger the body to deliver life-saving doses of the hormone. Mahdavi submitted a proposal and won the cash prize in 2013. He next launched a Pasadena start-up called Protomer Technologies to turn his idea into a real therapeutic.

The company aimed to develop a new synthetic molecule known as an agonist—a chemical substance that binds to a cell receptor and activates it to produce a biological response. In this case, Protomer’s drug would bind to the insulin receptor only when glucose levels rise, thanks to conditionally active binding moieties (parts of a molecule) that act as an “on” and “off” switch.

But Mahdavi and his team faced three major hurdles. The first was to create a synthetic molecule that could distinguish glucose from other sugars in the body. Another was to ensure that the therapeutic would interact with glucose but not so strongly that the agonist would become saturated and unable to detect subsequent spikes in blood sugar. The biggest concern, however, was overactivation: If a person were to indulge in glucose-rich soda or ice cream, the initial rush of sugar in the bloodstream could cause the therapeutic molecule to deliver too much insulin, dropping glucose levels precipitously and potentially causing hypoglycemia—a condition that requires immediate medical attention.

In the beginning, Mahdavi and his team focused on building new methodologies and tools to significantly increase the screening of potential therapeutic molecules and make it easier to identify which might be targets for modification; one such tool was their molecular evolution of peptide sensors (MEPS) platform. When one molecule did not work, MEPS allowed them to move on to the next candidate as quickly and efficiently as possible. “In searching for a solution, sometimes it’s hard to anticipate problems,” Mahdavi says. “We made no assumptions other than that we were not clever enough to predict every problem. Instead, my team and I took each concept and tried to fail quickly in every way possible until we ran out of failure modes.”

Mahdavi decided to base Protomer in Pasadena, a decision he believes helped the company to be successful. His mentor Tirrell, now Caltech’s provost and the Carl and Shirley Larson Provostial Chair, played an influential role in Protomer’s success. A decade before Mahdavi launched Protomer, Tirrell had launched his own biotech start-up and had appreciated the experience of developing a potential treatment for multiple sclerosis. He initially joined Protomer as a scientific co-founder, offering his perspective on how to approach the process of developing a synthetic receptor and speaking with potential investors.

“Alborz had a very good idea, and if his work could help people, I wanted to support it,” says Tirrell, who stepped away from Protomer when he became provost. “In general, there is a continuing effort at Caltech to make it appealing for our community to stay local and start their companies. Alborz and others have helped create an intellectually enriching and entrepreneurial environment here.”

Mahdavi also connected with Bassil Dahiyat (PhD ’98), the founder, president, and CEO of Pasadena biotech firm Xencor. Dahiyat showed Mahdavi how to build a drug-development program from the ground up. Mahdavi also met regularly with Mikhail Shapiro, Caltech’s Max Delbrück Professor of Chemical Engineering and Medical Engineering and a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Investigator, who offered advice. The two shared an office at MIT while Mahdavi worked as a research associate before graduate school.

“I don’t think people appreciate how lonely it is to be a start-up CEO,” Mahdavi says. “When things aren’t going well, it is helpful to have a close circle of trusted people to reach out to. The type of support that people at Caltech have for each other helps make sure we’re all successful.”

Lilly acquired Protomer in 2021, helping to accelerate clinical development. Today, Protomer’s glucose-sensing molecules are in clinical trials. As vice president of Lilly Research Labs, Mahdavi and his team are now using MEPS to fight or cure other critical diseases. The Caltech alum also shares his expertise while serving as a mentor to the Institute’s aspiring entrepreneurs. “The Institute’s faculty and alumni believed in me,” Mahdavi says. “That is the best form of support you can have, and I hope to do that for others.”