Rethinking Redistricting: Voting Experts Explain the Problem of Partisan Gerrymandering

This year, as the U.S. Supreme Court tackles a slew of hot-button topics, its justices are receiving advice from two Caltech professors on an issue with huge implications for the nation's politics: partisan gerrymandering.

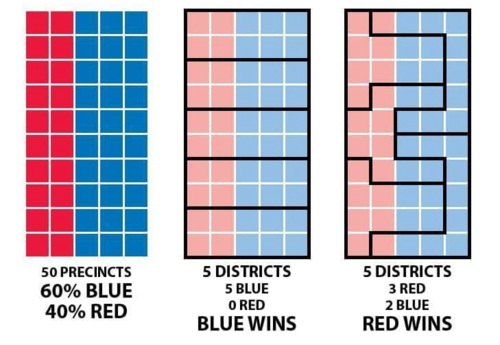

By adjusting the boundaries of electoral districts, political parties can gain votes and influence election outcomes dramatically. In this example, though the district is 60 percent blue, a redrawing of the boundaries results in the majority of the districts being controlled by red (far right).

Image: Steven Nass/Wikimedia

Morgan Kousser, the William R. Kenan, Jr., Professor of History and Social Science, along with Jonathan N. Katz, the Kay Sugahara Professor of Social Sciences and Statistics (both from the Division of the Humanities and Social Sciences), have helped prepare amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs in support of a group of voters from Wisconsin suing their state over an electoral map they say deprives them of their political voice.

That case stems from 2011, when Republicans redrew Wisconsin state-assembly districts in a manner alleged to keep Democrats out of power. In the 2012 election, Republicans gained 60 percent of the seats in the assembly while only receiving 49 percent of total votes cast.

In response, 12 Democratic voters in the state filed a lawsuit seeking to have the Republican-drawn map declared unconstitutional. The plaintiffs prevailed in district court, which ordered the state to draw a new electoral map. The state appealed to the Supreme Court, which agreed to take up the case. Oral arguments were held in October 2017 with a decision expected in 2018.

For Kousser and Katz, both of whom have served as expert witnesses in voting-rights trials for years, this Supreme Court case holds both personal and academic importance. Though they have sometimes found themselves on opposite sides of cases, they're in agreement on the negative effects of partisan gerrymandering.

Gerrymandering is achieved through adjusting the boundaries of districts to achieve desired electoral outcomes such as diluting the voting power of a racial or ethnic group, protecting incumbents from losing their seats to challengers, or keeping one political party in power.

Advances in computing technology have made gerrymandering much more effective than it was in the past, say Kousser and Katz. "They used to draw districts by hand using a slide rule," Kousser says. "Now you can spit out 10,000 district plans from a computer." Big data has also made it much easier for politicians to target which voters they want in a district, almost to the household level.

The last time a political gerrymandering case reached the Supreme Court, in 2004, a split court ruled against the voters, with swing voter Anthony Kennedy saying he believed partisan gerrymandering was an issue the court should decide if someone could develop an objective way to measure it.

There are four basic methods of gerrymandering, each with its own descriptive name:

Hijacking puts incumbent politicians from the same party who previously represented different districts into the same district so they have to run against each other.

Kidnapping moves an incumbent politician's voter base to another district, leaving them stranded in a new district with less support.

Cracking takes a group of voters and spreads them out across several districts to dilute their influence enough that they are not able to elect any representatives.

Packing crams as many of one type of voter into a single district so they're only able to elect one representative, rather than allowing them to influence electoral outcomes in several districts.

This is where Katz and Kousser come in.

Kousser's brief lays out a case that gerrymandering in its modern form is a serious threat to democracy in the United States, and implores the court to step into an area where it's traditionally been reluctant.

"The argument we're making is that the historical precedent of the court deferring to state legislatures on these issues doesn’t apply because the tools have changed," Kousser says.

Katz's brief proposes the court use something called the partisan symmetry test, which is the idea that a share of total votes should result in the same number of legislative seats regardless of which party received them.

"This is perfectly workable. I've argued this in court and it's been accepted," Katz says. "Now we're trying to convince Justice Kennedy that this is practical."

Kousser encourages other scholars and researchers to become involved in the political process as he and Katz have done. "Scientists are going to increasingly see issues they care about being litigated," he says. "Professors and intellectuals can get involved in shaping public policy through contributing to amicus briefs. It's a way for scientists to actually put their expertise to use shaping public policies."

As the creators of the maps fiddle with them to achieve their desired electoral outcomes, districts take on strange shapes. "If it’s a funny-looking district then it's probably a gerrymander," Kousser says.

The term gerrymander actually refers to those strange shapes. It was coined in 1812 by newspapers critical of then-governor of Massachusetts Elbridge Gerry, who signed a redistricting bill that benefitted his Democratic-Republican Party. One of the districts was said to be shaped like a salamander, and a political cartoon called it a "Gerry-mander."