Paying the Blood Price: How Medieval Europe Was Like a Mafia Move

How ordinary life in the early Middle Ages was a lot like The Godfather.

by Emily Velasco

If a hypothetical 30th-century historian wanted to learn about your 21st-century life, they would have a harder time than they would trying to learn about Ronald Reagan or Pope Francis, but that does not mean they would be totally out of luck. Even an average person leaves behind quite a paper trail.

This is exactly how Caltech’s Warren Brown, professor of history, learns about the lives of ordinary people in early medieval Europe—that period between the fall of Rome and the year 1000 that is often (though not quite accurately) called the Dark Ages. In his new book, Beyond the Monastery Walls: Lay Men and Women in Early Medieval Legal Formularies, Brown pieces together the contours of those people’s lives through the legal documents they left behind.

Among other things, the documents show that violence was a much more regular feature of their lives than it is for us. “We live today in a society where the state has a monopoly on the use of force,” he says. “If I were to come over and punch you, that would be illegal. But at a time and place when the state is much weaker than it is now, people had a fundamental right to use force on their own behalf to take vengeance or to defend themselves.”

Though violent acts could be expected, they were not unregulated. A person could only kill or harm another for what the community thought was just cause. Violence had to take place within a legal framework, and there was always a cost.

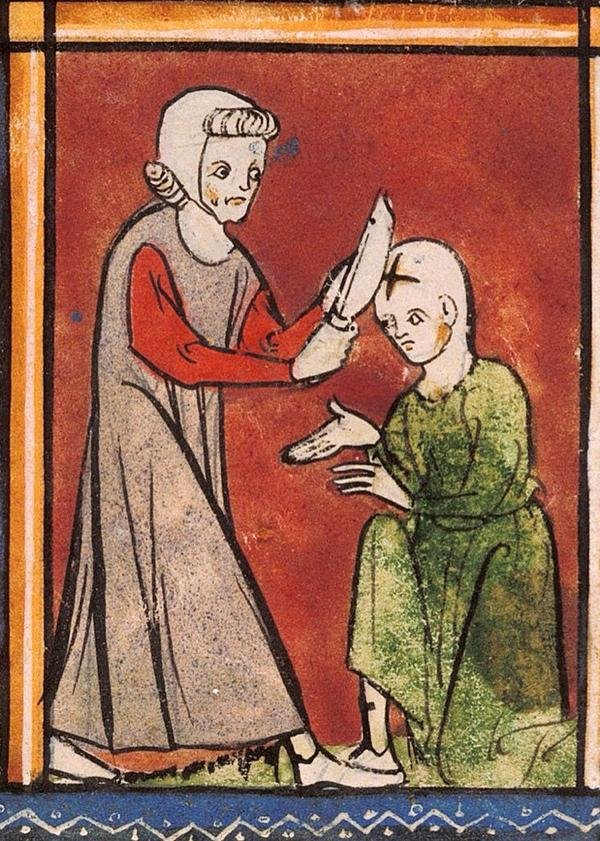

“If you killed somebody, you would have to pay for them. It’s called the blood price,” Brown says. “If I killed your brother, I may have thought I had a good reason, but you and your family are very angry with me, and you’re going to come after me unless I agree to pay you a certain amount of money to settle the debt. These amounts of money are specified in law. So, I’ll pay you the money, and you’ll write me a receipt that says you got it and that I’m free from any trouble about the matter. We only know about these receipts because they show up in the formularies.”

Brown also says patronage and nepotism were not just rampant, but an acceptable and necessary means for those without power to gain access to those who did. If you were a peasant with a problem that needed solving, you might appeal directly to your king, whether by getting someone to send a letter for you or by walking 60 miles to make your request in person at the king’s court. More often, however, you would appeal to your local lord, bishop, or abbot, who might have a relative who knew someone at court who could get the king’s ear.

“If you knew or were related to somebody who had power, or you knew somebody who was related to somebody who had power, you went to that person and you begged and pleaded, and that person would intervene on your behalf. It’s how you get things done,” Brown says. “And it happened at all levels of society. I’ve got a whole collection of letters written by a local lord in the 820s, where you can see him writing the most prosaic letters like, ‘So and so came to me and said he really would like to buy your pigs. Would you be willing to sell him your pigs?’ People were appealing up the chutes and ladders of power in a way that we today, I think, would look on with suspicion.”

If this sounds a bit like a mafia movie, with people asking favors of the don and others engaging in violent acts to settle their differences, you’re not far off. “It’s a little caricatured, but you can get pretty close to understanding the early Middle Ages by watching The Godfather,” Brown says. “The mafia also channels power along the lines of kinship, patronage, and protection, and it has rules regulating violence among its members. The difference is that it operates outside of the dominant system of law and order—and preys on it for profit. In early medieval Europe, it’s just simply how things worked.”