The Professor of Musical Comedy

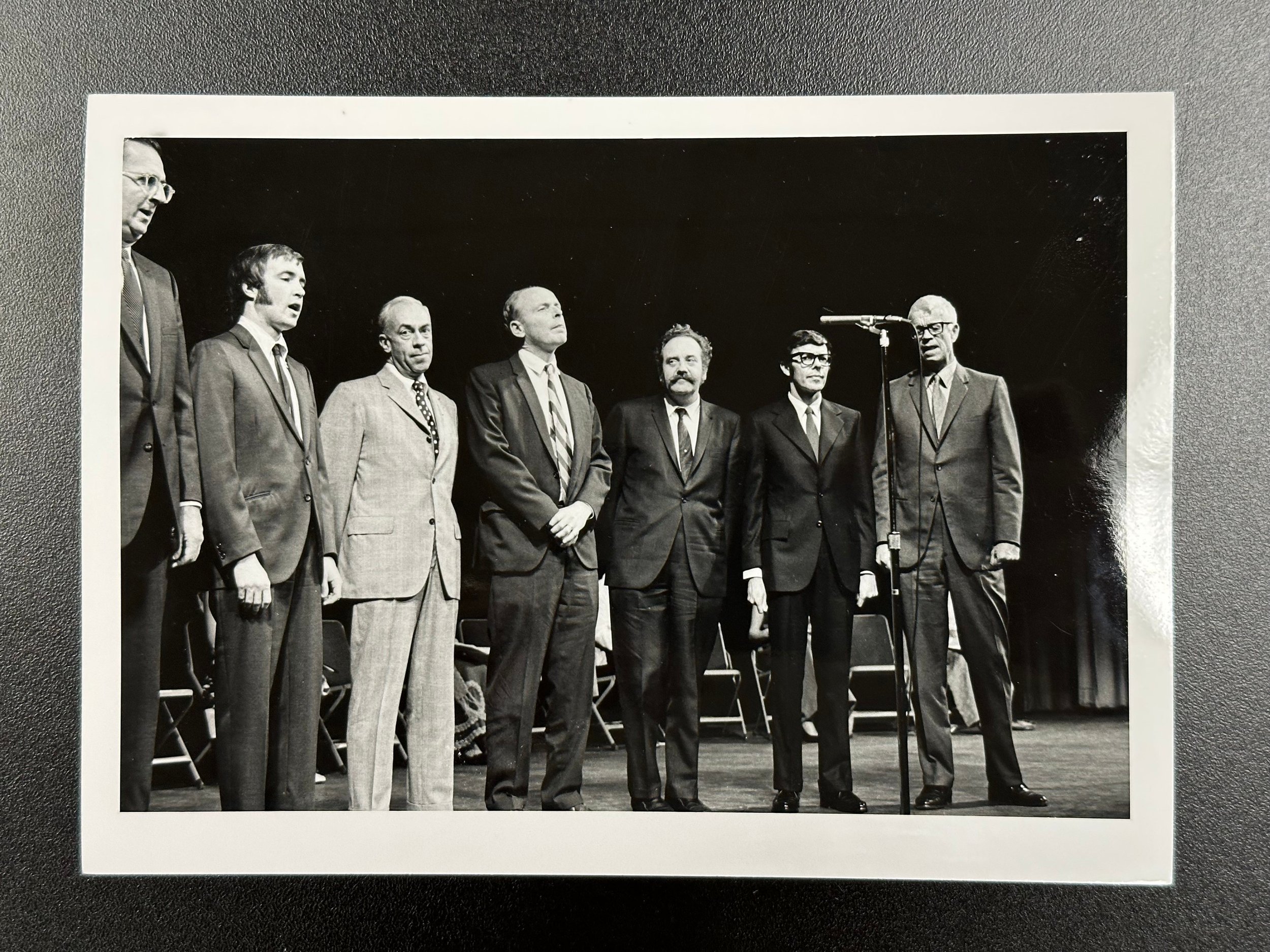

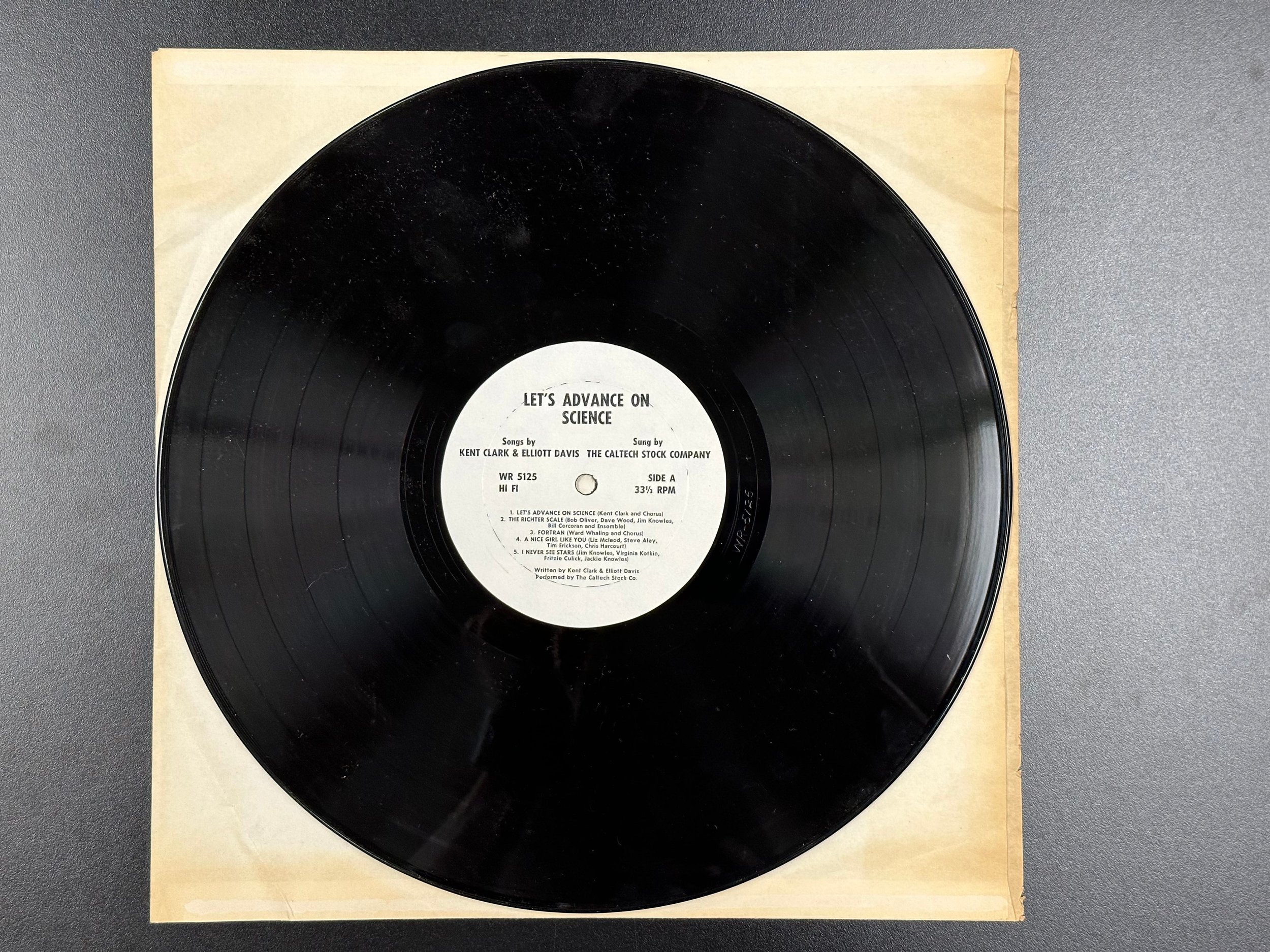

Former Caltech professor, J. Kent Clark holding a vinyl record of “Let’s Advance on Science.”

By Judy Hill

So said professor J. Kent Clark in a 1989 oral history interview for the Caltech Archives. By that definition, Clark certainly could write comedy and, over the course of a four-decade career teaching English literature at the Institute, he did exactly that, mostly in the form of musical shows that extracted hilarity from the serious matter of Caltech science.

Clark, who died in 2008, was a scholar of 17th-century English literature and politics who wrote deeply researched books on Goodwin Wharton, a 17th-century aristocrat, and his brother Tom Wharton, a Whig politician, as well as a historical novel, The King’s Agent. He was also a one-time chairman of the Beckman Committee that put on performing arts events and, in his words, Caltech’s “de facto commissar of culture.”

However, Kent Clark—nicknamed “Man Super” for his name’s resemblance to the superhero’s—is perhaps best known at Caltech for his musical comedies, which celebrated, and gently teased, the likes of Linus Pauling, George Beadle, and other eminent Institute scientists, while shining a fond light on the quirks of campus life.

Born in Utah in 1917, Clark caught the musical comedy bug while an undergraduate at Brigham Young University. “[The BYU students] had to entertain themselves,” said Clark. “They were out there on the frontier with professional entertainment miles away, so they had this tradition” of putting on shows. During summers, he honed his show business skills as a singing bellhop at a lodge in Bryce Canyon National Park before heading off to Stanford for his doctorate in English literature. Clark landed at Caltech in 1947.

When his daughter, Kay, began attending Pasadena’s Allendale Elementary, Clark began to collaborate with fellow parent Elliott Davis, a lawyer and musician, on humorous songs for the PTA shows. Word of these witty tunes made its way to the office of Caltech’s then-president Lee DuBridge, who, in 1954, asked Clark to put together a musical tribute to Linus Pauling, who had recently won the Nobel Prize for Chemistry.

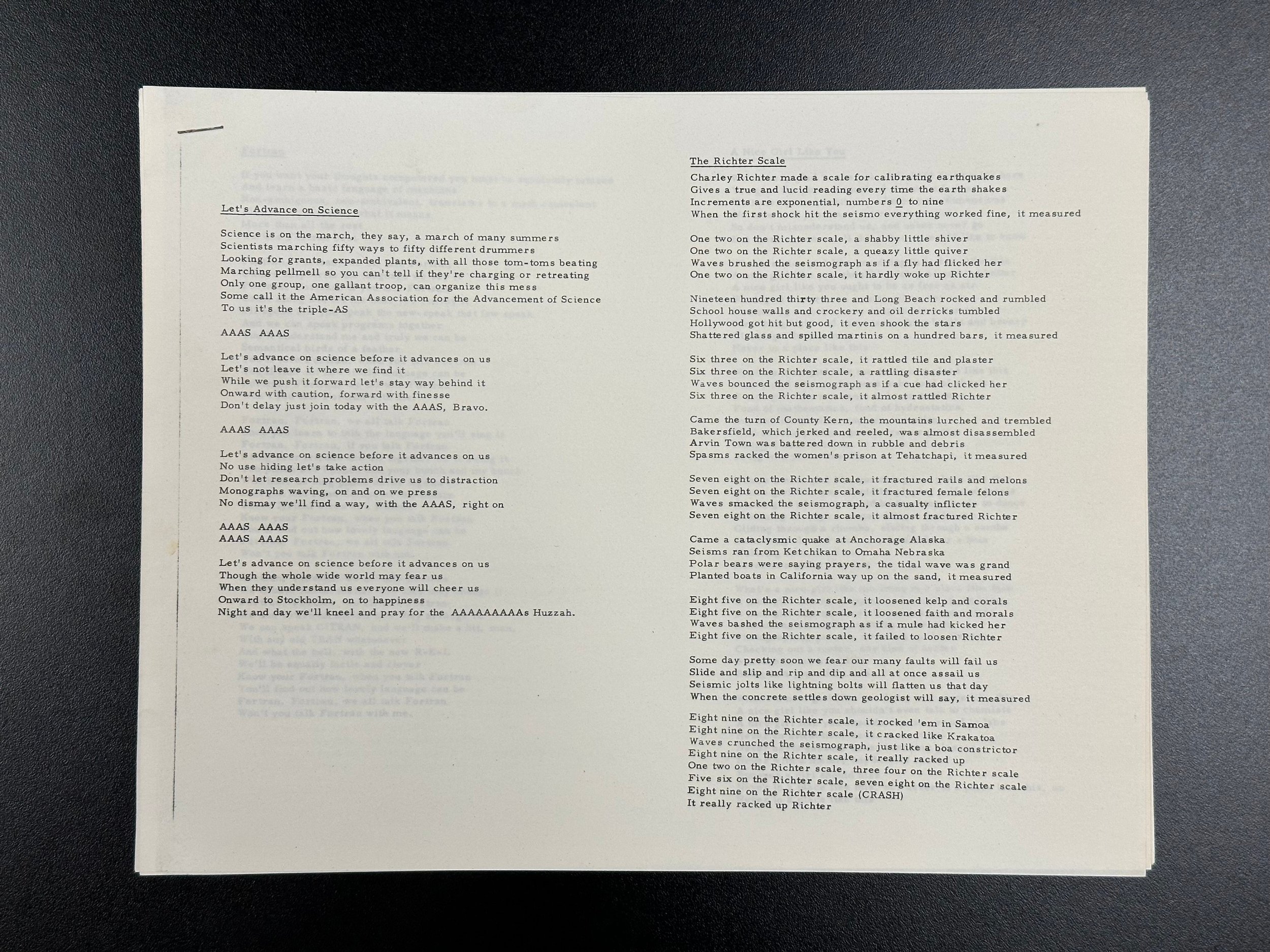

The next year, when Caltech hosted the annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Clark and Davis put together an entire full-length show, This is Science? “Let’s advance on science,” one of the songs urged, “before it advances on us.”

Davis scored the music and played the piano, while Clark came up with the lyrics. “Dad was not a guy who could tell you about chords or scales or anything like that,” says his youngest son, Don Clark, a journalist in Oakland. “He played no instruments, but I believe he actually made up the melodies. I think he would sing them to Elliot and Elliott would make them work.”

Clark created an ad hoc theatrical troupe called the Caltech Stock Co in 1955. It was made up of fellow faculty, staff, and students. It remained active for two decades. “One of the great things about Caltech is that it has a tremendous amount of theatrical talent,” said Clark in his 1989 oral history interview. “For musical comedy, you need people who can carry a tune—they don’t have to sing well, but they have to sing passionately.”

A show for DuBridge’s 10th anniversary at Caltech in 1956 featured the song, “For the Sake of the Republic,” which played on the idea that students come to Caltech from a sense of duty and self-sacrifice. “For the safety of the nation, we will stake our sanity,” goes the end of the first chorus, “And although we often rue it, we know someone has to do it, for the sake of the republic.”

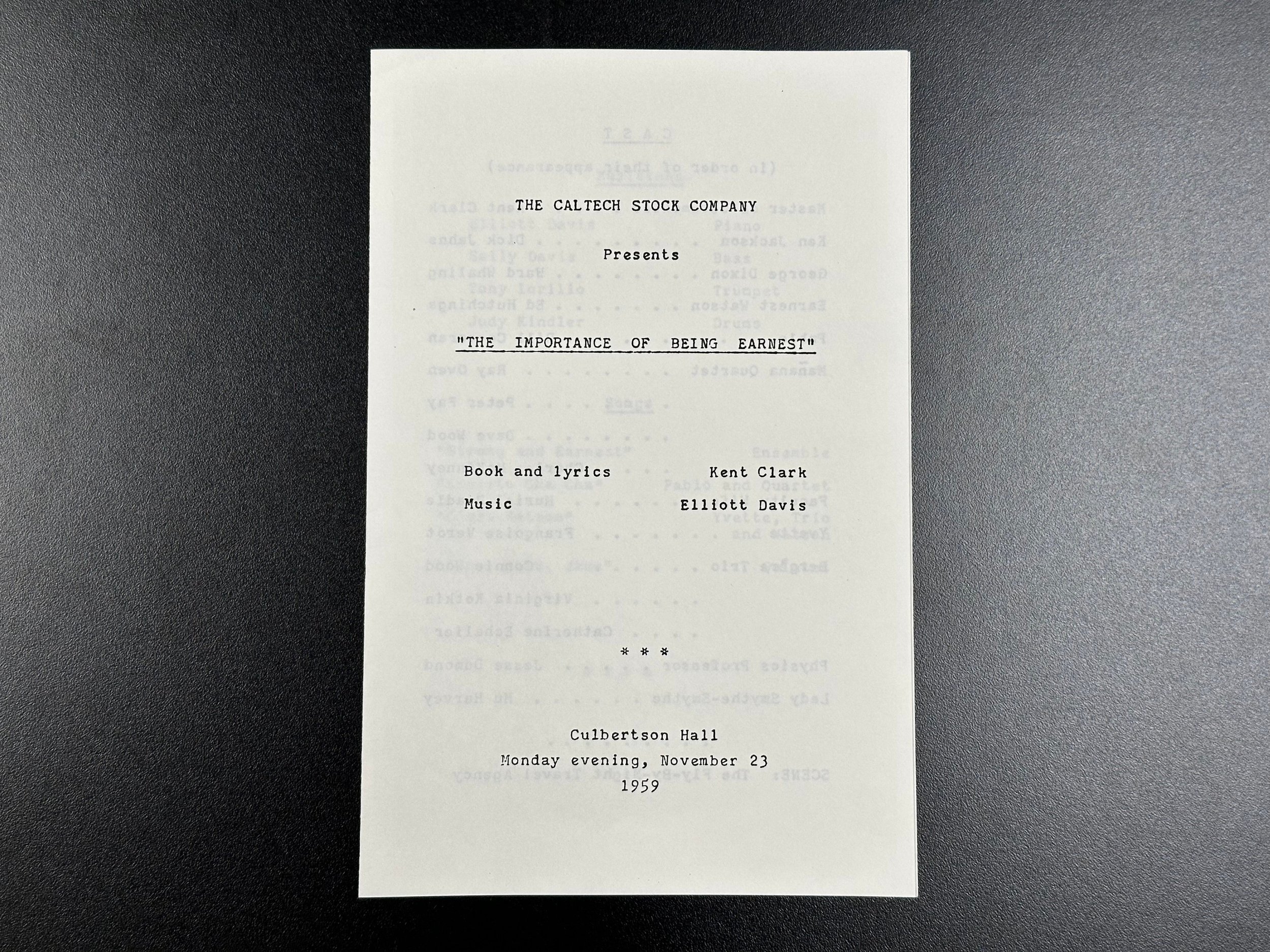

The Importance of Being Earnest followed, staged on the occasion of Earnest Watson’s retirement, and, in 1966, a second DuBridge show, which included the songs, “A View from DuBridge,” “Fortran,” and “The Richter Scale.” Much of the writing and rehearsing took place on the sands at Newport Beach, where Clark and his family often rented a summer place. Clark’s wife, Christie, daughter Kay, and family friend Darlene Oliver (the wife of Clark’s good friend, economist Bob Oliver) worked out the choreography. On the song “Fortran,” graduate student Cary Davids (PhD ’67), a physicist who went on to Argonne National Laboratory, played a rousing trumpet.

Caltech seismologist and physicist Charles Richter was apparently too shy to attend the show, though others in the audience heard how:

“When the first shock hit the seismo, everything worked fine. It measured:

One, two, on the Richter scale, a shabby little shiver.

One, two, on the Richter scale, a queasy little quiver.

Waves brushed the seismograph as if a fly had flicked her.

One, two, on the Richter scale, it hardly woke up Richter.”

Don Clark remembers the family home on Fillmore Street as filled with music. “They would have rehearsals at the house,” he recalls. “They would bash these things out on the piano that was bought for my piano lessons. They were sort of parties, you know—there was a lot of smoking and cocktails. Dad grew up in the jazz era, so the way his musical mind worked was like ’30s and ’40s jazz, and that’s kind of how the songs came out.”

Caltech during the DuBridge presidency felt like a family, too, in Kent Clark’s memory. “The DuBridges had this gemütlichkeit that made us a family,” he told Caltech Archives in 1989. “We were all in the same crazy enterprise together. … [I]t gave a sort of relaxed atmosphere all around. And that’s why, really, we got into the business of doing shows, because it was an inside family thing.”

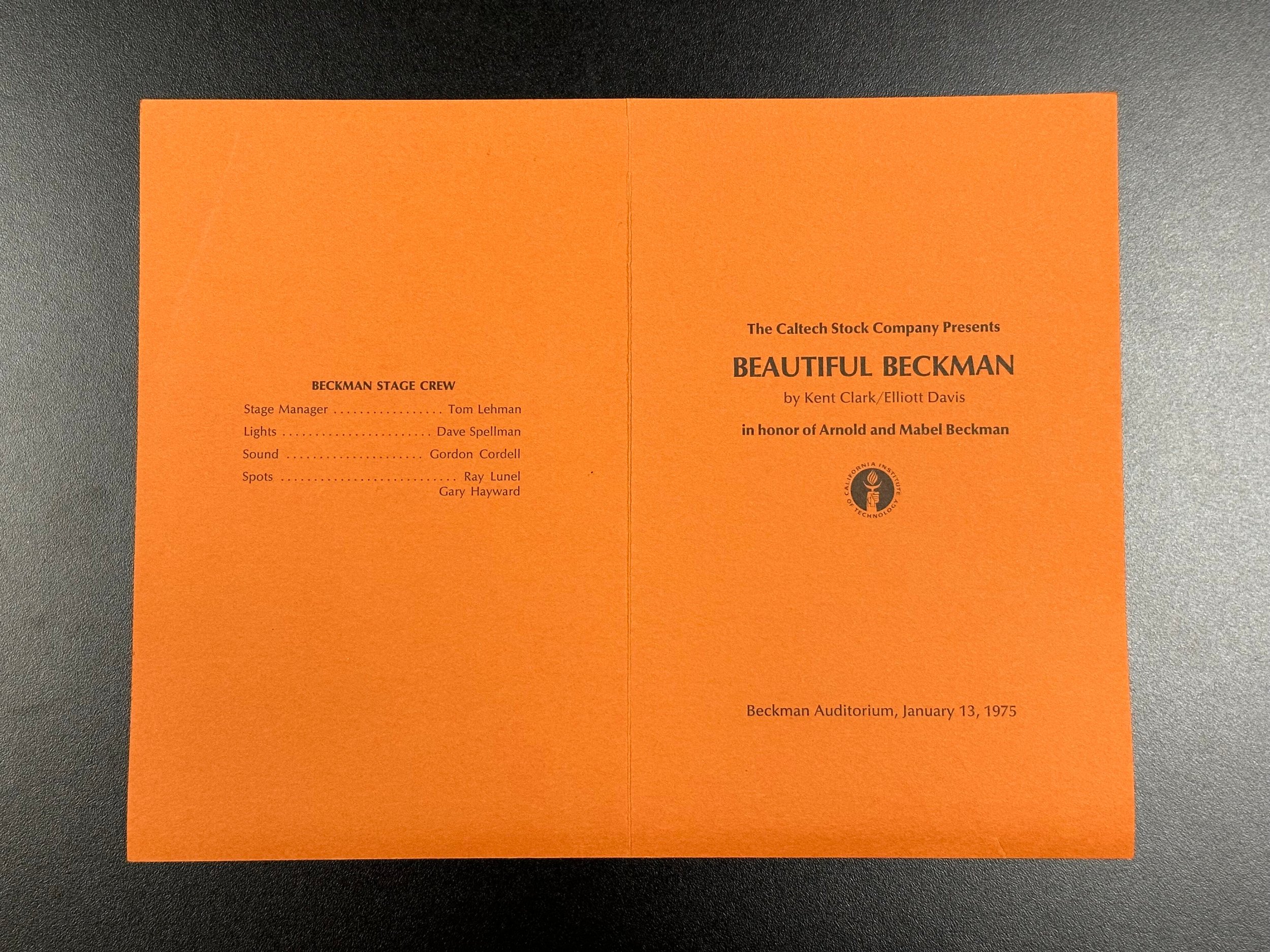

As the shows became larger and more complex, the musical accompaniment grew from just a piano to a small combo to a fair-sized orchestra. Don Clark, who plays guitar, remembers taking part in his father’s last major show, Beautiful Beckman (for Arnold Beckman’s 80th birthday), in the Beckman Auditorium in 1975.

“Humor is the other side of the truth,” said Kent Clark, who added that while the lyrics were supposed to be funny, they were based on observation and the contrast between the myth and reality of Caltech. “The lovely thing about Caltech,” he said, “is that both faculty and students … they get all this stuff, and they laugh. They can take it. They can make fun of themselves.”