Inside Look: Step Into the Office of President Thomas F. Rosenbaum

All image credits: Bill Youngblood

Caltech’s president takes pride in the importance of ideas and objects within his office.

By Omar Shamout

The life of a university leader involves meeting people. Lots of people. For Thomas F. Rosenbaum, a schedule of eight meetings a day is not unusual. Most take place in his office in the Parsons-Gates Hall of Administration, home to the Office of the President since 1983. When Rosenbaum arrived at Caltech in 2014, his first order of business was to ascertain what makes Caltech tick. So, he met with the Institute community—faculty, administrators, staff, and students—and listened. “Culturally, Caltech has its own nature, language, focus, structure, and ambitions,” he explains. “I had to learn about the ethos, and you do that by talking to people.”

The conversations have continued ever since. “I still believe firmly in giving people the opportunity to express their views and introduce their ideas. It’s important that you listen and that you be open to changing your mind. It’s part of the fun of this job.”

The president hopes his space reminds guests of Caltech’s values, which he says mirror his own. “The objects around the room reflect various experiences I’ve had both as a scientist and as a science administrator. There’s a mix of the professional and personal aspects that I hope comes through,” he says. “One thing I love about Caltech is that we’re not very hierarchical. We value people for their ideas, not for their positions. We know there are big stakes to what we do, and some of what’s here reflects that.” This sentiment is particularly evident on a bookshelf where a model of the Mars Perseverance rover is perched as if scrambling down a stack of books, some of which are about New York City, where Rosenbaum grew up. The rover is a NASA mission managed by JPL, which Caltech has operated for the space agency since 1958.

Humanity’s exploration of space has had an outsized impact on Caltech research, and it made a seminal impression on Rosenbaum as a child in the 1960s. He credits the Apollo missions with inspiring him to pursue a career in science.

“I was the perfect age to be influenced by the Apollo Moon program, and I followed it passionately,” he recalls. “I have memories of lying on the living room floor on July 20, 1969, eagerly waiting to see Neil Armstrong step off Apollo 11. Science was fun but difficult; it was admired by society, and you felt like you could make a contribution.”

Rosenbaum’s contributions have come both as an administrator and as a condensed matter physicist. His research seeks to understand the connections between the microscopic world, dominated by quantum mechanics, with the macroscopic world, governed by classical physics. “I also look at how quantum materials transition between ground states,” he says. “And whether it is possible to induce new nonequilibrium states.”

While there are a few heavy-duty science tomes dotting the shelves, Rosenbaum keeps his physics materials in his Norman Bridge Laboratory research office. Many of the science books in his Parsons-Gates office are geared toward general audiences. “There are lots of books on the physics of golf, the physics of baseball, things like that,” he says. “I’ve taught courses on the physics of sports. It’s much more interesting for students to hear about throwing a football in a spiral rather than an abstract discussion of torque and angular momentum.”

When he vacates the president’s office next summer, he will move his books and memorabilia to new shelves in a different space. What he will lose is the opportunity to speak with as broad a swath of the Caltech community as he does now. “Caltech is special because of the people who are here,” Rosenbaum says. “Although I’ll be closer to my scientific colleagues, I won’t have the same level of interaction with the rest of the talented people across campus. I’ll miss that.”

New York Yankees banner

Rosenbaum spent most of his formative years in New York City’s borough of Queens, home of the New York Mets. So, how did he wind up as a fan of the archrival Bronx Bombers? “It is not logical, because I could bicycle to Shea Stadium—and I did. We would go watch the Mets,” he says. “But the first baseball game I went to was in 1962, maybe ’63, at Yankee Stadium. The Yankees won 9–1 over the Cleveland Indians, and I’ve been a Yankees fan ever since.”

New Yorker cartoon by Sidney Harris (published July 16, 1973)

Rosenbaum has been reading The New Yorker magazine since he was in grad school, though the cartoons caught his attention much earlier. “I looked at the cartoons when I was a kid because my father had a subscription,” he recalls. “Even though I’m a physicist, I’m a Luddite. I like to actually hold the printed version of The New Yorker. When I travel, I bring a stack of them with me.” This framed cartoon was a gift from Rosenbaum’s two sons. “I think you have to be a scientist to find it amusing,” he says.

Wright brothers photo and Mars surface photo

Perhaps nothing in the president’s office reflects Caltech’s impact on science and engineering more strikingly than these two side-by-side images. The first is a photo from the New York Times archive of Wilbur Wright testing an early biplane on a sandy beach in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, circa 1903; the second, a close-up image of Mars’s sandy surface taken by NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, a mission managed by JPL. Though the Wright brothers were not affiliated with Caltech, the Institute helped advance their astounding invention and propel humankind to the stars—and the Red Planet—opening new windows on the universe. “I like the contrast,” Rosenbaum says.

Brass replica cannon

Rosenbaum made this cannon during his graduate studies at Princeton University, where he earned his PhD in 1982. “I learned how to use a machine shop to make equipment for my experiments,” he says. “This was the project to be certified to work in the shop. The guy who ran the shop was named Bob Puglisi. When you were done, he’d take the cannon and slam it on the table. It was scary; if it didn’t fall apart, you passed. I insist that all my students learn how to machine. In addition to learning the actual skill, you’ll also learn enough so that when you go to a professional machinist and ask them to make you something, you’ll understand the sensible limitations on your request.”

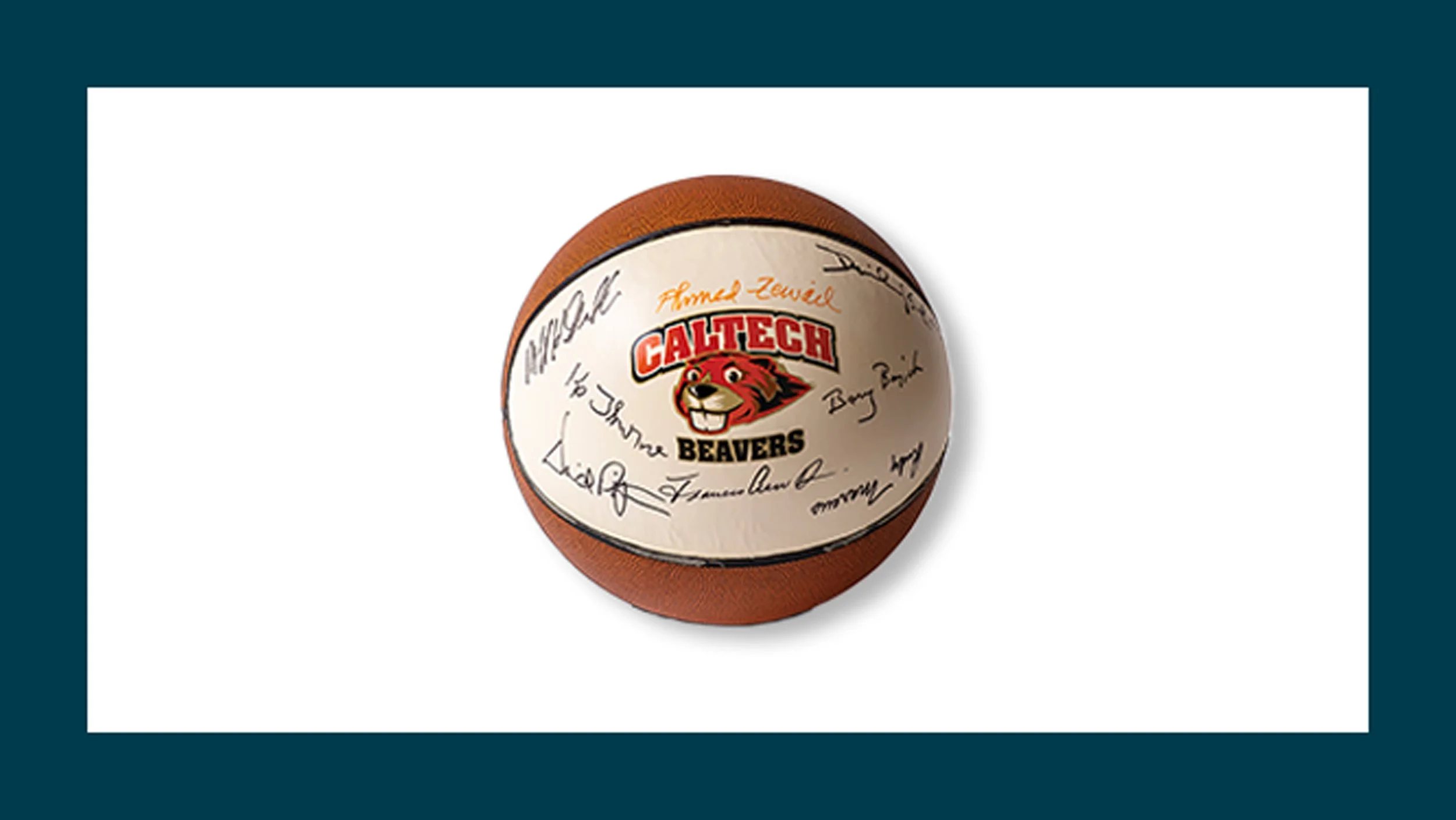

Basketball signed by Caltech Nobel laureates

Rosenbaum, an ardent basketball fan, has asked every Caltech Nobel laureate he has interacted with since he arrived to sign this ball. “Tragically, three of the individuals who have signed this are no longer with us: Ahmed Zewail [Linus Pauling Professor of Chemistry], Bob Grubbs [Victor and Elizabeth Atkins Professor of Chemistry], and David Baltimore [President Emeritus and the Judge Shirley Hufstedler Professor of Biology],” he says. “Having their signatures here is very meaningful to me.”

Melted sand from the Trinity nuclear test and a brick from the University of Chicago squash court

Two pieces of Manhattan Project history can be found in Rosenbaum’s office. The first is a piece of melted sand from the site of the Trinity nuclear blast in Los Alamos, New Mexico, a gift from David Groce (BS ’58, PhD ’63), a member of the Caltech Associates. The second is a sandstone brick from the squash courts underneath the University of Chicago’s Stagg Field, the site of the first nuclear reactor, known as Chicago Pile-1. Rosenbaum received the brick while working at the university. “I also have a little piece of the graphite that was part of the nuclear pile, but I don’t have that here in the office,” he says.