What the Past Can Tell Us About Forecasting the Future

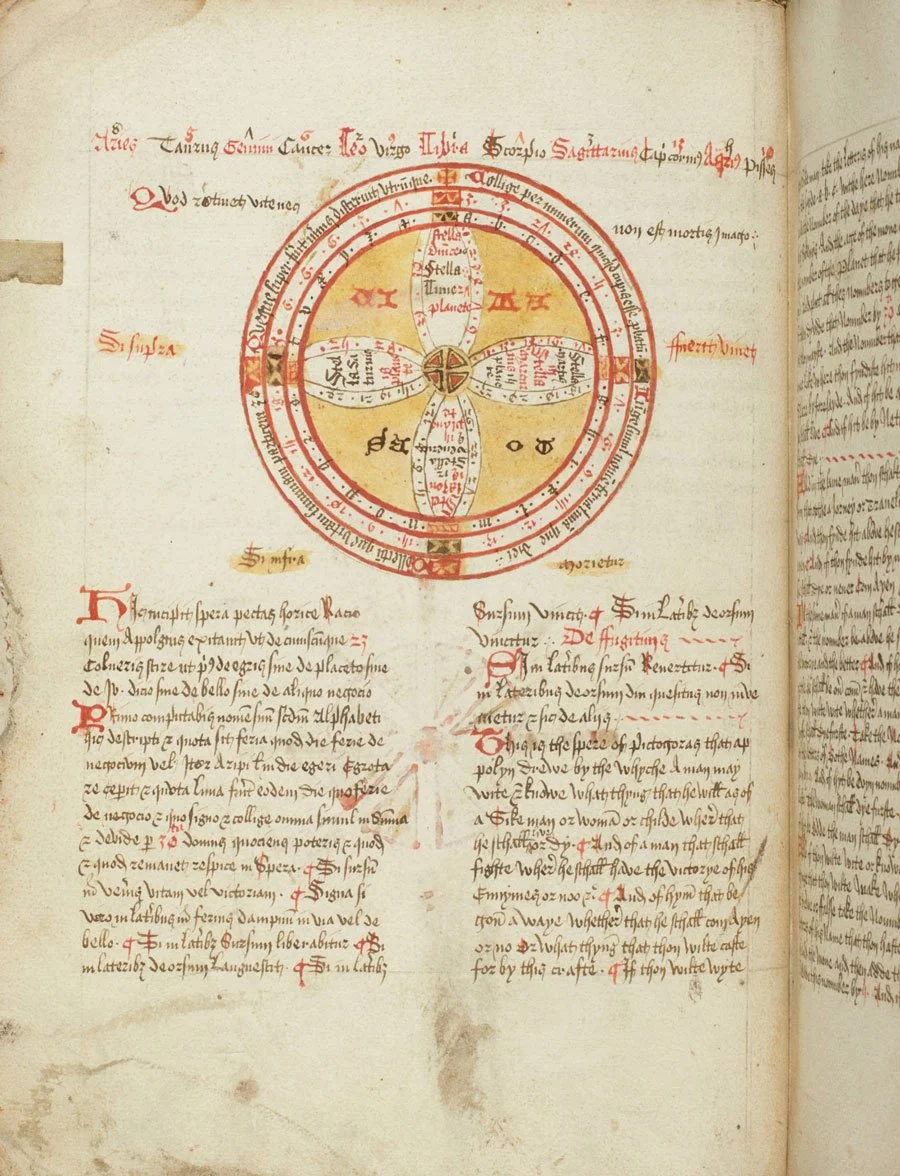

Detail of The Sphere of Life and Death. San Marino, Huntington Library, MS HM 64, folio 15v.

Jennifer Jahner is revealing the history of predictions by digging through ancient and medieval texts.

By Katie Neith

Professor of English Jennifer Jahner has spent much of her career exploring the histories of law, rhetoric, philosophy, and literature in the European Middle Ages. But it was a very recent event—the COVID-19 pandemic—that helped form the thesis of her current book project, Arts of Conjecture: The Medieval Origins of Modern Prediction.

“I had been researching premodern concepts of experimentation but didn’t realize I was working on a history of prognostication and conjecture until COVID brought home just how deeply our sense of the world is shaped by faith in the reliability of our forecasting models,” says Jahner, who is also dean of undergraduate students and the Fletcher Jones Foundation Distinguished Fellow in British History and Culture at The Huntington Library, Art Museum, and Botanical Gardens. “The experience had me reflecting on the period I research and asking, What did a ‘forecast’ look like in an era before probability calculus and statistics? I realized that many of the core questions we struggle with today are present in these much earlier periods of history but reveal themselves in different ways—some familiar, some radically distinct.”

Recently, Jahner presented some of her latest findings during a lecture at The Huntington called “Futures Past: Lessons from the History of Prediction.” In her talk, she used examples from The Huntington’s manuscript collection to explore the medieval roots of the modern forecasting models we use to predict weather, the economy, the spread of pandemics, and much more. By looking at premodern predictive technologies—like astrology—she said she hoped to provide “some lessons for the existential questions we face today: questions of futurity, survival, and our fraught struggle to balance individual and collective well-being in our era of algorithms and artificial intelligence.”

To explore how astrology and other applied sciences of the time helped people navigate uncertainty in the Middle Ages, Jahner highlighted the work of Egyptian astronomer and mathematician Claudius Ptolemy. Contained in The Huntington archives is a copy of his most consequential work, Almagest. Written around the year 150, his theory of a geocentric universe acted as a basic guide for European and Islamic astronomers for nearly a millennium. Together with his companion volume on astrology, the Tetrabiblos, Ptolemy’s Almagest helped define the workings of a predictable universe.

“Astrology was not pseudoscience for Ptolemy nor for the many, many intellectuals he influenced over subsequent centuries,” Jahner explained. “It constituted, instead, the necessary corollary to astronomy’s precision. Astronomical calculations might get us closer to fundamental truths about physics and divinity, but they do not account well for the contingency and uncertainty that defines our daily experience on this planet.

“I realized that many of the core questions we struggle with today are present in these much earlier periods of history but reveal themselves in different ways—some familiar, some radically distinct.”

“For thousands of years, astrology answered the same questions we now use statistical modeling to predict: How long might I live? Does this new year promise net gains or economic downturns? How likely are floods or fires?” Jahner continued.

Citing multiple examples from medieval texts, Jahner built a strong argument for these predictive arts of the time—which offered a wide array of answers to questions both mundane and momentous—as being early forms of what we now think of as an algorithm.

“I'd like to suggest that certain aspects of premodern predictive beliefs survive in our own data-saturated present,” she said. “Prediction … has always constituted a place where science struggles tenaciously with its own ambitions and limitations, its future and its past.”

To drive this point home, Jahner concluded the lecture by showing a diagram housed at The Huntington that dates to the late 1400s called The Sphere of Life and Death. It represents a simple machine for telling the future by using numbers assigned to things like letters, dates, and calculations based on questions to determine whether a patient was more likely to live or die. Then she showed an image from a 2023 study published in Nature Computational Science by researchers in Denmark who used information about life events such as health, education, occupation, and place of residence to build an algorithm that predicts the likelihood of early mortality. Both the medieval and modern figures spoke to similar desires to predict and control uncertain life events, and especially our own deaths, said Jahner.

To learn more about how COVID-19 shaped her current work, you can watch Jahner’s 2022 Watson Lecture, “The Rhetoric of Chance in Times of Pandemic,” here.

“Each of us can decide for ourselves how eager we are to peer into this particular algorithmic crystal ball, but the model reminds us that the future is a story we tell, not a fate we await,” she said. “And our ending for this story is one we’ve been trying, and failing, to write for a very long time.”

Jahner is spending the 2023–24 academic year immersed in the ancient texts of The Huntington Library as the Fletcher Jones Foundation Distinguished Fellow, one of 13 yearlong fellowships that the research institute awards annually. Established in 1985, the fellowship is intended for a full professor who teaches in the field of British history or literature.

“The chance to be at The Huntington for a full academic year is something of a dream come true,” Jahner says. “Working with archival collections always has a profound impact on a project; each manuscript is unique and thus informs one’s research in unique ways. Caltech has also made me an inveterate interdisciplinary humanist. I can’t imagine working now in any other way, so the biggest impact so far has certainly come from my cohort of long-term fellows. They are at all stages of their careers, working on a fascinating range of projects, and I’ve learned a huge amount from them.”