A Cache of Chemistry Models

While today’s undergrad can conjure up a molecular structure on a computer screen in a matter of seconds, for most of the history of scientific education physical atomic models have been basic building blocks for teaching and understanding chemistry. And Caltech has played a key role in that history.

Early models, dating back as far as the 1860s, featured balls representing atoms and sticks signifying chemical bonds. In the 1950s, Caltech’s Robert Corey and Linus Pauling, along with UC Berkeley’s Walter Koltun, led the design of a new type of three-dimensional model. These space-filling calotte models (also known as CPK models), which became standard issue not only in laboratories but in science classrooms the world over, are made up of individual balls that represent atoms; the size of each sphere is proportional to the size of the actual atom, and its color linked to the type of atom.

Not only were the molded-plastic CPK models developed at Caltech commercially successful, they also established a popular color convention for atoms in molecular models, called the CPK Coloring Scheme—with red for oxygen, blue for nitrogen, white for hydrogen, yellow for sulfur, and black or gray for carbon.

A sizable collection of CPK model components can still be found on the Caltech, largely due to the efforts of Larry Henling, staff crystallographer in Caltech’s X-Ray Crystallography Facility. Henling has preserved drawer upon drawer of the molded-plastic atoms and their connector links as well as design drawings, blueprints, contemporary photos, and correspondence related to the models.

Does he have a favorite? “Glycine,” says Henling. “It is an amino acid, the simplest one, but wasn't easy to solve at the time the structure was done. In the crystal it is a zwitterion—an overall neutral molecule but with a positive charge at one end and a negative at the other."

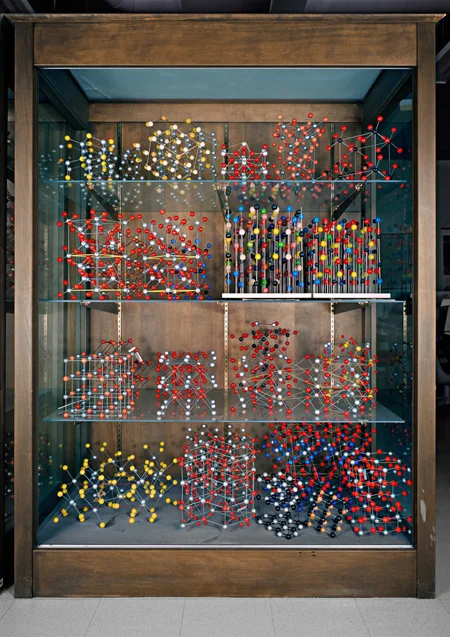

Shelves and display cases in Henling’s office show off other models that have found their way to Caltech over the years—the ball-and-stick and skeleton variety, as well as more unusual cardboard iterations—while a table near the window of the crowded space is given over to an outsize model of copper metal used by Linus Pauling in lectures.

Though Henling can’t recall when the models were last used, it feels important to him to keep them. “The models and blueprints are historical reminders of the time and effort Caltech researchers, many of whom are now forgotten, put into developing an understanding of molecular structures,” Henling says. “Today, scientists do the same with just a push of a computer button.”

—Judy Hill

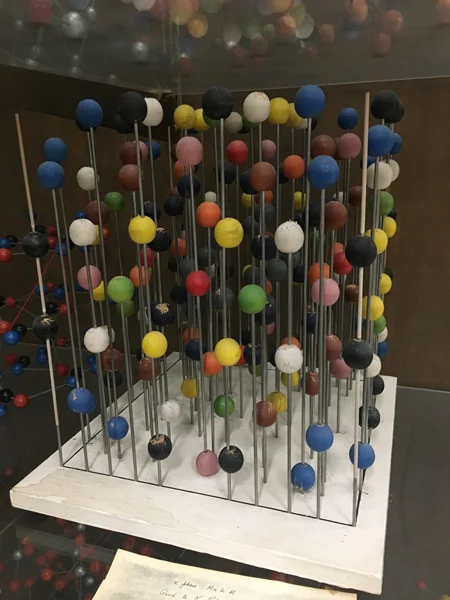

A model of the α phase of MnSiAl (Manganese Silicon Aluminum), an intermetallic compound. The vertical rods are merely to hold the atoms. The structure is cubic so that all three cell edges are equal and all angles are 90˚. The colors of the balls represent the different symmetry positions in the unit cell, not the kind of atom. The structure was published in 1966.

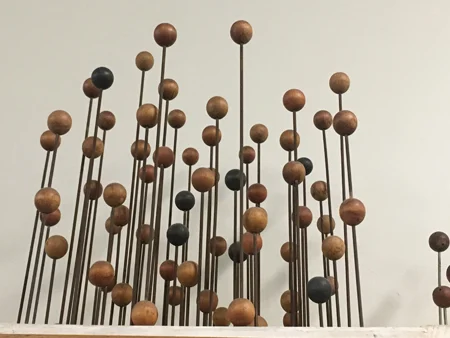

A model of copper metal, with each ball representing an atom. The unit cell (basic building block of the crystal) is a face-centered cube (a cube with eight atoms at the corners and six atoms in the faces) as indicated by the balls connected by rods. Each copper atom has 12 nearest neighbors. This model, stacked as a three-sided pyramid or tetrahedron, is explained (at 8:45 minutes) in a 1957 NSF video by Linus Pauling.

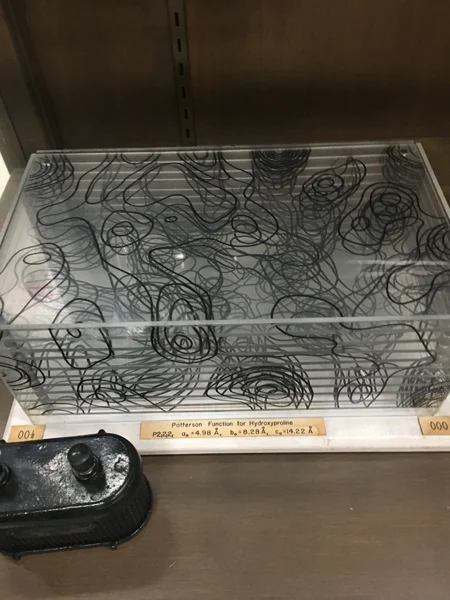

A 3-D Patterson map used in solving the structure of the amino acid hydroxy‐L‐proline. The contours are hand-drawn from a computer printout on Plexiglass sheets. The map was used to obtain the structure of the molecule from X-ray photographs of a crystal. When X-rays are scattered by crystals, the amplitudes of the X-rays can be readily measured, but not their phases. Both are needed to calculate an electron density map, which indicates where the atoms are; a Patterson map is a way to solve this phase problem.

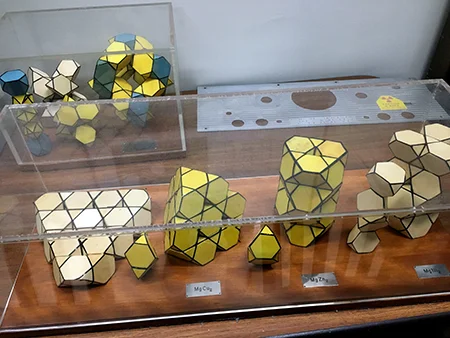

Polyhedron models of various intermetallic compounds (MgCu2, MgZn2, and MgNi2 in front). A common motif is the Friauf polyhedron represented by a truncated tetrahedron with four triangular faces and four hexagonal faces. Despite the simple formulas, some of these compounds (e.g., NaCd2) have extremely complicated crystal structures, which are still being studied today.

A wooden ball and stick model of Aureomycin lies in a parts box along with plastic atoms and molecular fragments from disassembled models gathering dust as they fruitlessly await incorporation into new models.

A faded model of γ-brass, an alloy of copper and zinc (Cu5Zn8). There are four types of brass balls: 20 Cu (red and orange) and 32 Zn (green and black).

A display case showing various ball-and-stick models; the different colors represent different elements. Most are common minerals and were manufactured by the Leybold company for teaching purposes. On the left side of the third shelf down can be seen a model of cubic NaCl (table salt) with alternating red and silver spheres. On the left of the second shelf down are two models of quartz (SiO2) illustrating the non-superimposable mirror images of left- and right-handed quartz.